Sammy Munsch, Internship Program Manager, Office of the Secretary of Higher Education for the State of NJ

Kristen Gallo, Executive Director of Career Services, Temple University

Introduction

In the spring of 2021, Temple University successfully launched a program to financially support students undertaking unpaid internships in the summer of 2021. The program was in response to two main considerations: the broader impact of unpaid internships on students; and the timing of a second consecutive summer during a pandemic that severely impacted student opportunities to gain meaningful work-integrated learning experience. The program ultimately funded 24 students in roles throughout the city of Philadelphia and broader Delaware Valley region, with the vast majority in non-profits, arts, and educational settings. To gain the buy-in for this program like this we needed to establish the need for financial support for students in unpaid roles, plan the logistics, partner with numerous stakeholders at the university, and ensure follow up and evaluations took place.

While multiple factors aligned to make the program possible, which will be explained in further detail, first and foremost we needed to establish the benefit that could come from funding students taking unpaid internships. Unpaid internships are a hotly contested phenomenon. Supporters cite better career outcomes for students who participate in an internship, regardless of compensation. Critics cite the legality of working without compensation or in some cases for college credit, for which the student may need to pay tuition to their institution to earn. The benefits of internships for college students can include higher starting salary in the first post-graduation position, more job offers and shorter time to employment post-graduation (Collins, 2020). Unpaid internships, however, may not have these same benefits (Crain, 2016) and favor privileged students with the financial means to support themselves during the internship (Mohan, 2019). Knowing that employers often seek students with some form of experience often through internships or co-ops while in college (NACE Staff, 2017), the barriers to accessing roles that increase social capital, networking opportunities, and qualifications cannot be ignored.

Taking in this information and translating it for university leaders was a first step in the process to launching the program. We also needed to develop some of our own goals, defining clearly how Temple students specifically would benefit, to create the strongest buy-in for the idea. Adding to the potential benefits resulting from access to opportunities, we also saw the chance to support organizations in our city of Philadelphia doing work in the public interest. Philadelphia has arts institutions, cultural organizations, community and education non-profits, and other impactful organizations. At the same time Philadelphia is cited as one of the poorest large cities in the United States (Shields, 2020). We looked to our mission statement which includes a commitment to “promoting service and engagement throughout Philadelphia, the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the nation, and the world.” When we melded together the idea of supporting students and supporting organizations doing good in our city, we had a strong case.

Setting the Stage

Providing some context about the structure at Temple University will help with understanding the steps we took to achieve the goals of this program. At Temple, the Career Center reports up through the division of Undergraduate Studies, which in turn reports directly to the Provost. Within the portfolio of Undergraduate Studies there are eight departments including the Career Center, Fellowships Advising, the University Honors Program, the Academic Resource Center, the Student Success Center, Pre-professional Health Studies advising, ROTC, and the university’s General Education program. The commonality among these departments is that each serves as a central resource for students across the university. As a portfolio, Undergraduate Studies seeks to offer wide support to help Temple Students be successful and each department works with all colleges and schools at the university.

Career services at Temple University is a hybrid model. The university Career Center reports through Undergraduate Studies. A broader group, called the Career Network, consists of professionals embedded within the colleges and schools at the university that focus on career development for their respective student populations. Career services departments and staff within the colleges and schools report up through the leadership of their college or school. The university Career Center works closely with these colleagues across the university.

Getting Started

In February 2021, at a bi-weekly meeting of all the directors within Undergraduate Studies, we learned that the division had some overage budget from the year. This was because the entire university had been remote since March of 2020. Funds normally earmarked for operations, programs, and supplies were not used in the usual way. Planning was underway within the Provost portfolio to plan on how funds would be used. Once our team learned about this, the conversation turned to how we could use the funds to support students. We all knew the challenges being faced by many people, now almost a year into the pandemic, and were particularly aware of these challenges among our student population. The group discussed some immediate ways we might be able to support our students financially and the idea for a university-wide funding program for students participating in unpaid internships took off.

First, we needed to know the feasibility of using the funding to go directly to students as a way to support their unpaid summer internships. For that, we required buy-in from the budget team within the Provost’s portfolio. We knew we needed a plan and some strong evidence around successes of this type of program to submit a proposal. With the spring 2021 semester underway, we had little time to execute this program. We needed to ensure we aligned our program with similar stipend programs across the university and utilized the expertise of several colleagues to do so. We collaborated with:

- Associate Vice Provost of Research, who manages the Merit Scholar Stipend Program

- A colleague in the career center of the College of Liberal Arts, managing a similar stipend program, to ensure that our requirements aligned

- Director of Scholar Development and Fellowship Advising for guidance on creating an application and the process for stipend disbursement.

The expertise of these colleagues helped us align with similar stipend programs at the university. After two discussions within a week we had a timeline, process, and a student application ready for review.

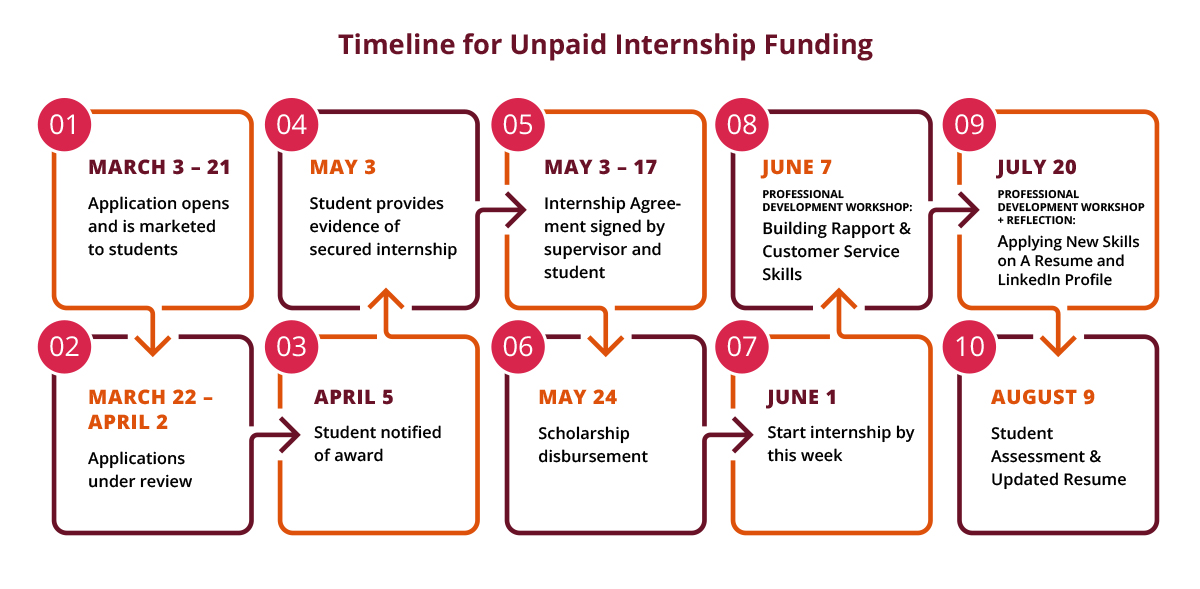

With support from the Vice Provost and a solid proposal we were approved for an allocation of $50,000 to fund stipends for students participating in unpaid internships during the summer of 2021. Under the leadership of Sammy Munsch, Assistant Director of Internships and Experiential Education at the time , work shifted to executing the timeline, marketing content, student applications, rubrics for evaluation of applicants, and the disbursement of funds. We quickly realized the need to collaborate with the Director of Student Financial Services to ensure that the funds were distributed as efficiently as possible and that we had a process to review students’ applications. Bringing this partner in right at the start was crucial to later steps we took. Now we were ready to get the word out to students.

How We Did It

Students were invited to apply to this program through various channels including the Career Center website, Handshake, official university social media channels, and through outreach of student facing departments. We focused on “word of mouth” advertising through campus partners to ensure that we targeted students in majors/programs likely to be seeking unpaid roles and could demonstrate a need for funding. We considered an email blast via Handshake to the entire undergraduate student population but determined there was a high likelihood we would have been overwhelmed with student applications, and the expedited timeline was a hurdle. Additionally, we sought to focus on organizations including non-profits, arts and education, or community organizations that benefit the Philadelphia community which further required targeted communication.

The application was developed using Microsoft Forms and focused on three main questions. Students were also asked to upload a resume, but their resume was not included in the selection process, rather this was used to help us understand general career and academic goals.

- “The purpose of this fund is to facilitate students’ engagement in unpaid internship opportunities that may not be possible without this support. Please explain how this funding creates this opportunity for you.”

- “What are your career goals? How does this internship fit in with your academic/professional plan?” (Max 400 Words)

- “Have you already committed to a Summer 2021 Internship?

- If yes, please describe your internship.

- If not, please explain how you plan and timeline for searching and applying for an internship.”

Within a 2-week window of time, 247 students from across disciplines applied to participate in the program. The applications were reviewed by nine staff members from the Career Center over the course of one week. Applicant names were removed from the reviewers copy of the applications to avoid the presence of implicit bias. The reviewers utilized a rubric to judge only the first two questions of the application. Leading the selection process, Sammy Munsch, Assistant Director of Internships and Experiential Education at the time, worked with the reviewers to determine level of need, if applicants fit populations targeted by the program, level of professional readiness, and whether an internship has been secured. Applicants did not have to secure an internship before applying for the program, but they did need to secure the internship on their own and by a certain date to receive funding.

After the initial review, the 247 applicants were narrowed down to 50 applicants. At this point we worked closely with the Director of Student Financial Services to identify the students with the greatest financial need. It is important to note here again that Student Financial Services was a critical partner. To avoid taxes being withheld from the stipend, the financial award was officially deemed a “scholarship”. This means that if students were carrying a balance the stipend would have automatically been applied to their balance, rather than being available for students to use directly. After working with Student Financial Services, we narrowed the applicant pool to our top 25 stipend recipients and allotted 10 spaces for a potential waitlist.

Following the final selection of the recipients, students accepted were notified and required to agree to all relevant Student Financial Services policies regarding scholarship awards. Ultimately, 25 students were selected to receive the stipend and one student later rescinded the offer due to securing a paid opportunity. The chosen recipients provided verified proof of their unpaid internship lasting for at least 150 hours during the summer months. The students received the $2000 stipend by May 25th. Non-selected applicants were provided with career coaching resources and scholarship resources when notified about the status of their application.

To verify the students’ internship, the recipients provide three documents: job description, offer letter, and Internship Agreement signed by themself and their employer. All recipients agreed to participate in professional development workshops, complete a final post-experience evaluation, and submit an updated resume reflecting their summer experience at the end of the summer.

Upon review of the post-experience evaluation, 21 of 24 recipients completed the evaluation. The questionnaire included 10 questions that asked about the student’s career competency development during their internship. Additionally, there were three open ended questions included at the end of the evaluation to encourage the students’ reflections.

- We’d like to learn more about the skills you’ve grown during your internship. What skills did you develop while in your internship and how did you develop them?

- What is the most important thing you learned from this internship experience?

- Please explain how receiving the stipend helped you perform in this internship?

We are continuing review the evaluations, in order to warrant offering this program for summer 2022. Our evaluation plan will include theming and coding the free response answers. This information will be used both to advocate for the continuation of the program and to inform us about professional development topic areas that might be incorporated into the educational components throughout the summer.

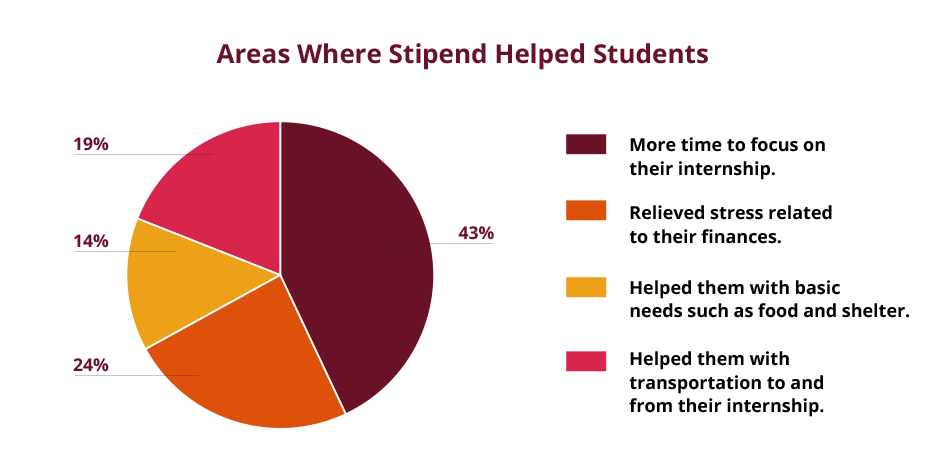

It should also be noted that students identified four areas in which the unpaid internship stipend helped them perform in the internship.

- Approximately 43% of students indicated that the stipend provided more time to focus on their internship.

- Approximately, 24% of students explained that the stipend relieved stress related to their finances.

- Approximately 14 % explained that the stipend helped them with basic needs such as food and shelter.

- Finally, 19% of the students indicated that the stipend helped them with transportation to and from their internship.

Timeline

Lessons Learned

This program was called a “unicorn initiative” by a colleague at the university. It is unheard of to launch a program in just four weeks, especially one that required numerous levels of buy-in and support. Along the way there were a number of lessons learned that we will benefit from and anyone considering a program like this should consider.

Top 5 Takeaways

- Support from leadership is essential to getting such a program off of the ground. We were lucky to have some initial interest that we strengthened with data and examples. This required us to adjust the proposal and focus depending on the role of the person reviewing it. While this was more work it allowed us to appeal to the key interests of those involved and everyone felt it was a win-win.

- Resources are not just financial. A dedicated staff member, or members, are needed to manage the project. This was a fast moving project, but even with more time, it is necessary to ensure someone is at the helm who can manage different partners and pieces of the process.

- Target your outreach. We had 25 spots available and received 247 applications. Over 100 applications came in during the 24 hours before the application deadline. We had students trying to submit late applications. We wanted to be mindful of the capacity of our team and other departments involved, while also meeting the core objectives of the initiative.

- Be prepared for some pushback. Some campus partners felt this program was inappropriately asking the university to shoulder the burden of compensating students for unpaid internships resulting in an implicit endorsement of unpaid internships. We also had discussions about whether positions at for-profit companies should be considered. To support our decision to allow any student with an unpaid internship to apply we were ready with research and best practices.

- Evaluate and have data ready. To get the pilot program running and now advocating for a second year, data and information have been key. Our student evaluation was a helpful tool to demonstrate success last year and we hope to add an employer evaluation component if the program is funded again.

The hope is that Temple University recognizes the value of the internship funding for summer, unpaid internships and will renew the commitment as a regular part of the Temple University’s Career Centers commitment to seek new ways to support our Owls in their professional development and to build upon the success if this pilot program.

Sources

Crain, A. (2016). Understanding the impact of unpaid internships on college student career development and employment outcomes. NACE. https://www.naceweb.org/uploadedfiles/files/2016/guide/the-impact-of-unpaid-internships-on-career-development.pdf

Collins, M. (2020, November 1). Open the door: Disparities in paid internships. NACE. https://www.naceweb.org/diversity-equity-and-inclusion/trends-and-predictions/open-the-door-disparities-in-paid-internships/

Mohan, P. (2019, August 21). How unpaid internships hurt all workers and worsen income inequality. Fast Company. https://www.fastcompany.com/90388911/how-the-unpaid-intern-economy-feeds-income-inequality

NACE Staff (2017, April 5). Employers prefer candidates with work experience. NACE. https://www.naceweb.org/talent-acquisition/candidate-selection/employers-prefer-candidates-with-work-experience/

Shields, M. (2020, December 16). The changing distribution of poverty in Philadelphia. Economy League of Greater Philadelphia. https://economyleague.org/providing-insight/leadingindicators/2020/12/16/phlpov19