Dr. David Stumbo, Ed.D., CSP, OHST, Eastern Kentucky University

Abstract

Postsecondary internships can be highly beneficial to student interns, host employers, and universities. This study sought to better understand the quality of internships performed by occupational safety students at Eastern Kentucky University through a survey of intern supervisors. Supervisors also provided data on the key internship indicators of salary, intention of making a job offer, academic preparedness, and suggestions for the professional development. Results indicate that supervisors provided high ranks for their interns’ performance. Analysis of the results indicate that several opportunities for improvement of internships exist on the part of host employers and universities.

Keywords: internships, occupational safety and health, workplace safety

Introduction

This article provides the results of a mixed methods study to better understand the nature of internships completed by students enrolled in undergraduate and graduate occupational safety degree programs at Eastern Kentucky University. Data gathered from surveys completed by Internship Supervisors is presented, and implications are discussed.

Occupational Safety and Health (OSH) Profession:

Within many organizations, an OSH professional fulfills a specialty management function that requires various interpersonal and technical knowledge, and skills, making completing post-secondary education essential. A substantive survey of OSH professionals conducted by the Board of Certified Safety Professionals (BCSP) and National Safety Council (2020) found that 79% of respondents reported having a bachelor’s degree or higher. The career outlook for OSH professionals is good, with the Bureau of Labor Statistics (2021) estimating that job opportunities for occupational health and safety specialists will see a 7% growth from 2020 to 2030, equating to about 8,800 jobs.

The Role of Experiential Learning:

Described as how academic theory is integrated with practical application in the workplace by Garvey & Vorsteg (1992), internships are considered a means for “integrating academically acquired knowledge and skills within the real world, problem-solving context of the workplace” (Bowen & Drysdale, 2017, pg. xvii). Internships have been described as a high-impact educational practice when properly administered (American Association of Colleges and Universities, 2020) and, therefore, a positive influence on academic and career success (Hora, Chen, Parrott & Her, 2020). The recognition that internships can provide a viable means for talent acquisition (Green, 2019; Bane, 2018; Greene, 2014) may further contribute to an increased awareness of the importance of internship experience (Bender, 2020).

OSH Internships:

Internships have long been considered appropriate to the OSH profession, with Hale, Piney & Alesbury (1986, pg. 9) declaring that internships belong in the curriculum of OSH degree programs because “occupational safety and health is by its nature ‘applied.’” The American Society of Safety Engineers (ASSE) and the Board of Certified Safety Professionals (BCSP), leading professional organizations, have called for the inclusion of experiential education as a core requirement for baccalaureate degrees in occupational safety (Hudson & Ramsay, 2019). The literature indicates that numerous university degree programs offer internships as optional coursework, if not a requirement (Fender & Watson, 2005; McGlothin Jr., 2003; Madigan, Johnstone, Cook, & Brandon, 2019; Iske Jr., Weller & Lengfellner, 2017). Other studies have signaled the significant role internships play in the curricula of OSH degrees (Ferguson, 1998; Derrick & Fender, 2009; Wybo & Van Wassenhove, 2016).

Benefits of Internships:

Internships provide positive outcomes for each principal stakeholder involved: students, employers, and post-secondary institutions (Velez & Giner, 2015). For students, internships can represent powerful learning experiences, allowing for the application of knowledge and providing opportunities to practice skills in real-world situations (Ambrose & Poklop, 2015). Neill (2010) added that internships can provide students with a better awareness of organizational variability, establish professional networks, and help them determine what they do not want in a career. Students who complete internships will likely derive a competitive advantage over other job seekers. For example, Collins (2021) reported that employers extended job offers to 80% of students who interned for their organizations. Employers reported that an internship experience was considered the “most influential factor” (Gray, 2021, para. 1) when all other candidate qualifications were equal.

Broadly, colleges and universities benefit from internships by “connecting with the professional world and bridging the boundary between school and workforce” (Tucciarone, 2014, pg. 30) and Karji, et al. (2020) held that internships boost the reputation of the university. More existentially, a trend of diminishing enrollments has highlighted the role internships can play as a viable means for greater competitiveness with other institutions (Weible, 2009). Unfortunately, benefits from internships derived by universities at the department level are not well characterized. One of the few studies which provide such specificity, authored by Weible & McClure (2014), surveyed the deans of business programs. Findings noted a positive influence on teaching relative to measures such as increasing faculty knowledge and improving classroom discussions. Interestingly, the study also indicated that opportunities offered by internship programs, such as expanded financial development of the school and professional experiences for faculty, were unrealized.

Employers enjoy several potential benefits should they elect to host interns. The first is a relatively inexpensive source of labor (Scheuer & Mills, 2016). Another is that the internship period can equate to an extended interview process should the employer wish to offer a full-time position to the intern (Galbraith & Mondal, 2020). Similarly, time spent during the internship period is used by some employers for the completion of some, if not all, of the typical onboarding phase. This approach might be referred to as pre-onboarding. With some initial employee orientation completed during the internship, in-depth training can occur during post-internship employment. Overall, employers can more rapidly “develop a highly skilled technical workforce” (Iske Jr., Weller & Lengfellner, 2017, pg. 37). Challenges must be considered, such as Niman & Chagnon’s (2021) caution that, due to the variety factors at play, internships “may be nothing more than a wasted opportunity as the responsibilities assigned and the tasks performed look more like busy rather than substantive work” (pg. 89). In balance, 82% of employers reported that they would employ the same or more interns over the previous year, despite the challenges posed by the pandemic (Gardner, 2021).

OSH Internships at EKU:

EKU offers a Bachelor of Science degree in occupational safety and a Master of Science degree in safety, security, and emergency management, each delivered concurrently online and on campus. Both degrees offer credited courses for OSH internships as electives. Students from these programs interned for employers in manufacturing, distillery, construction, petrochemical, insurance, and government industries. Internships must adhere to standards set by the National Association of Colleges and Employers (Eastern Kentucky University, 2021) and academic credit is awarded at an exchange rate of 1.0 credit hour per eighty internship hours completed.

OSH students are tasked with obtaining their internship position much like a regular job, first locating internship opportunities posted on commercial websites, through interviews at the university’s job/internship fairs, faculty referrals, and other means. Most then complete an application and interview for the internship position the same way as any full-time position. Once a student obtains the internship, it is administered through Handshake®, a web-based application that carries and tracks an approval process overseen by the student’s Faculty Internship Coordinator, Internship Supervisor, and EKU Career Services Administrator before registration into a credited internship course.

The Faculty Coordinator is a professor in the OSH department who ensures that the internship aligns with the educational objectives of the student’s degree program. The student’s Internship Supervisor, typically a manager for the host employer, ensures that the internship details relative to the host employer are accurate before issuing approval. Finally, a Career Services Administrator then verifies that all administrative provisions required by the university have been satisfied. As part of the approval process, students must complete an Internship Agreement which requires their promise to adhere to several conditions, such as compliance with the host employer’s requirements such as sexual harassment and time and attendance policies. Students must also authorize a Waiver of Liability, Assumption of Risk, and Indemnity Agreement for the internship.

Study

Research Objectives:

The research objectives for this study were as follows:

- Better understand the performance of OSH Student Interns as provided by their Internship Supervisors.

- Better understand key indicators for OSH internships as provided by Internship Supervisors (i.e., salaries, intention of making a job offer, academic preparedness, and suggestions for the professional development).

A subordinate utility for the study could be for the university to use findings to help establish operational baselines from its measures to which subsequent data can be compared, and trends recognized. Similarly, opportunities for improvement to the university’s internship program might be identified, applied, and addressed. Findings might also interest employers who may not realize the existence of such a program and the potential benefits of hosting an OSH intern. Finally, other post-secondary institutions that offer OSH-related degree programs but do not offer internships or do not recognize their substantial value could find the utility of the information provided here.

Research methods:

Data

Data for this study were collected as convenience samples from the Internship Supervisors of OSH Student Interns by the EKU Office of Academic and Career Services. Data ranged from Fall 2019 through Fall 2021, including Spring, Summer, and Fall terms. The data set was comprised of one hundred completed internships. Internships that were not completed due to the effects of the COVID19 pandemic and other factors were excluded. The response rate from Internship Supervisors was particularly good at 80% (n=80).

Instrument:

Internship Supervisors were asked to provide feedback on their Student Interns’ performance via a request sent by email that included a hyperlink to a survey form located within Handshake®. Questions were created by EKU Career Services, using the University of Cincinnati’s Experience-Based Learning and Career Education survey as a model, along with input from Faculty Coordinators and the EKU Advisory Board. Section 1 of the survey carried scale and open-responses questions, while Section 2 carried count and open-response questions.

Section 1: Ratings:

This section was designed to gather data to help characterize OSH interns’ job performance. Questions were organized into seven domains: Proactivity, Professionalism, Interpersonal Skills, Communication Skills, Critical Thinking, Delivering Results, and Overall Performance. Internship Supervisors were asked first to rate their intern’s performance and then elaborate on the rating using an open-response text box.

The text of each survey question guided respondents toward the focus and intent of each question. For example, the guidance provided for the domain of Critical Thinking noted: “For this survey, critical thinking includes critical reading, evaluating situations, decision-making to solve problems, application of classroom learning, and learning on the job, to the extent they apply to the intern’s role.” See: Figure 1: Internship Supervisors’ Survey.

Figure 1: Internship Supervisors’ Survey

Ratings:

Struggling: The student struggled to meet job/employer needs.

Developing: The student often met job/employer needs.

Performing: The student consistently met all job/employer needs. Excelling: The student was praised for exceeding expectations.

Q1. PROACTIVITY:

For this survey, proactivity includes motivation, positive attitude, and initiative, to the extent they apply to the intern’s role. Please explain your answer on this student’s proactivity using examples from their internship experience.

Q2. PROFESSIONALISM:

For this survey, professionalism includes punctuality, integrity, responsibility, and response to supervision, to the extent they apply to the intern’s role. Please explain your answer on this student’s professionalism using examples from their internship/co-op experience.

Q3. INTERPERSONAL SKILLS:

For this survey, interpersonal skills include positive relationships with everyone, teamwork, and active listening, to the extent they apply to the intern’s role. Please explain your answer on this student’s interpersonal skills using examples from their internship experience.

Q4. COMMUNICATION SKILLS:

For this survey, communication skills includes speaking, writing and presenting, to the extent they apply to the intern’s role. Please explain your answer on this student’s communication skills using examples from their internship/co-op experience.

Q5. CRITICAL THINKING:

For this survey, critical thinking includes critical reading, evaluating situations, decision-making to solve problems, application of classroom learning, and learning on the job, to the extent they apply to the intern’s role. Please explain your answer on this student’s critical thinking using examples from their internship/co-op experience.

Q6. DELIVERING RESULTS:

For this survey delivering results include, prioritizing goals, time management, use of resources and technology, adaptation to change, and producing quality work.

Options for response used the following ratings: Excelling: The student was praised for exceeding expectations, Performing: The student consistently met all job/employer needs, Developing: The student often met most job/employer needs, Struggling: The student struggled to meet job/employer needs. These were coded with values as follows: Excelling = 4, Performing = 3, Developing = 2, Struggling = 1, and then descriptive statistics were calculated.

Section 1: Open-responses:

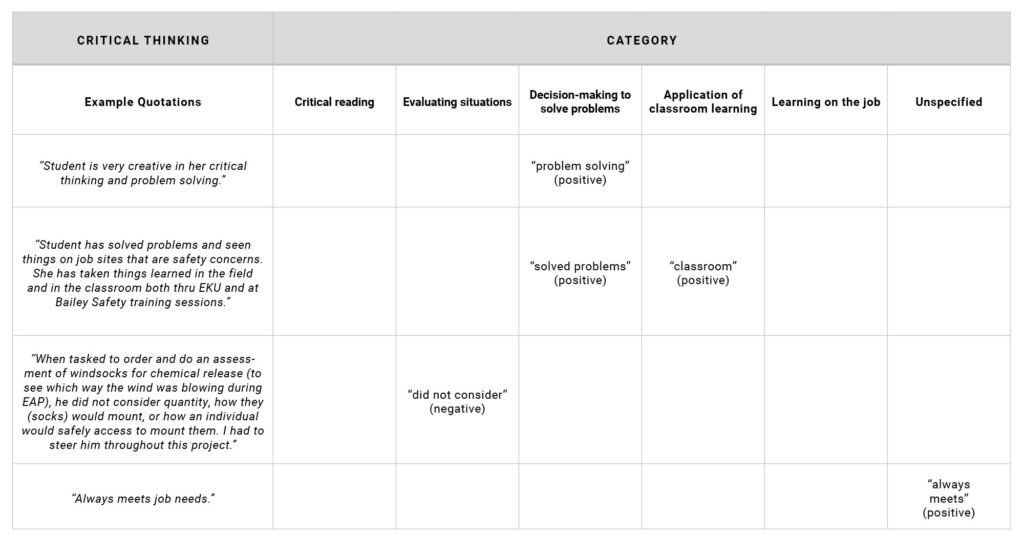

Analysis of open-response questions utilized the specific guide terms provided by each question. For example, for Critical Thinking, the question held, “For this survey, critical thinking includes critical reading, evaluating situations, decision-making to solve problems, application of classroom learning, and learning on the job, to the extent they apply to the intern’s role.” In that case, coding corresponded to the five guide terms from the question: Critical Reading, Evaluating Situations, Decision-Making to Solve Problems, Application of Classroom Learning, and Learning on the Job.

An additional code category, Unspecified, was included, which would capture responses that seemed to align to the domain but did not align well with the guide terms. For instance, the domain of Critical Thinking found responses from Internship Supervisors who used the specific term “critical thinking,” but that exact term was not among the guide terms for the question. Also, all such responses were categorized as either positive if the response appeared to indicate the Internship Supervisor’s approval of the intern’s performance or negative if the response appeared to indicate that the Internship Supervisor did not approve of the intern’s performance. An example of the process of analysis used for the Critical Thinking domain is found in Table 1: Example of Open-Response Analysis.

Table 1: Example of Open-Response Analysis.

Section 2:

Section 2 carried three count and one open-response question of specific interest to

this study. Count questions gathered data concerning the Student Intern’s pay, whether or not the host employer intended to extend a job offer to the Student Intern, and if the Student Intern’s academic program had prepared them for the internship. The open-response question sought the Internship Supervisor’s suggestions for the Student Intern’s professional development. The count questions were analyzed quantitatively, and descriptive statistics were generated, while the open-response data were analyzed using a coding process like that used for Section 1’s open-response questions discussed above.

Limitations:

Because convenience sampling was used to gather data, results may not be reliable representations of the general population. Additionally, biases typical to surveys, such as nonresponse bias from Internship Supervisors who chose not to participate in the study may have affected the results (Cowles, 2019).

Results and Implications

Results of Section 1: Rating:

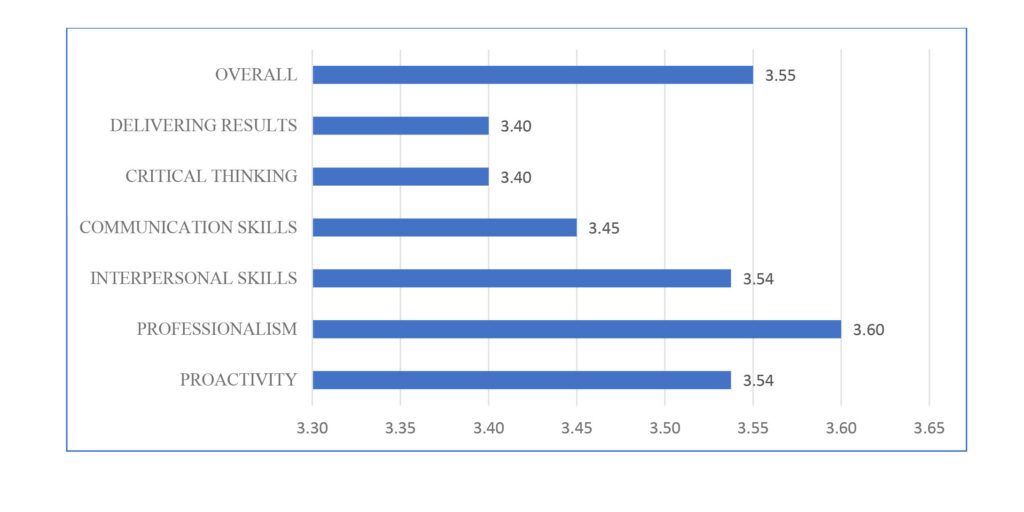

Supervisors provide the Overall rating of their interns, on a scale of 1 to 4, at an impressive average of 3.55 (SD = 0.63). This average reflects well on the qualities of Student Interns and their academic programs. Ratings for the other six domains: Proactivity, Professionalism, Interpersonal Skills, Communication Skills, Critical Thinking, and Delivering Results, are displayed in Figure 2, Key Domains.

Figure 2, Key Domains

Among the domains, Professionalism produced the highest average rating (M = 3.60, SD = 0.58), while the lowest average rating was tied between Critical Thinking (M = 3.40, SD = 0.67) and Delivering Results (M = 3.40, SD = 0.72). The implications of the Professionalism domain’s high ratings, if the question’s guiding terms (e.g., punctuality, integrity, responsibility, and response to supervision) were instructive to respondents, indicate that Student Interns are strong in those qualities.

Critical Thinking’s lower rating may indicate opportunities for improvement on the part of academic preparation. Critical thinking was identified by Arum & Roksa (2011) as a skill in which a substantial percentage of undergraduates were not showing meaningful improvement during their first two years of college, so this finding should not be surprising to academics. It should be noted that this study did not gather the class rank (i.e., sophomore, junior) of the Student Interns. While many host employers are recognized as preferring Student Interns who are at least juniors, this is anecdotal. Data that considers employer feedback against Student Interns’ class rank is an opportunity for future research. The domain Delivering Results was also rated relatively lower by Internship Supervisors. The analysis of the associated open-response question, discussed in more detail below, may aid in understanding this finding.

Results of Section 1: Open Responses:

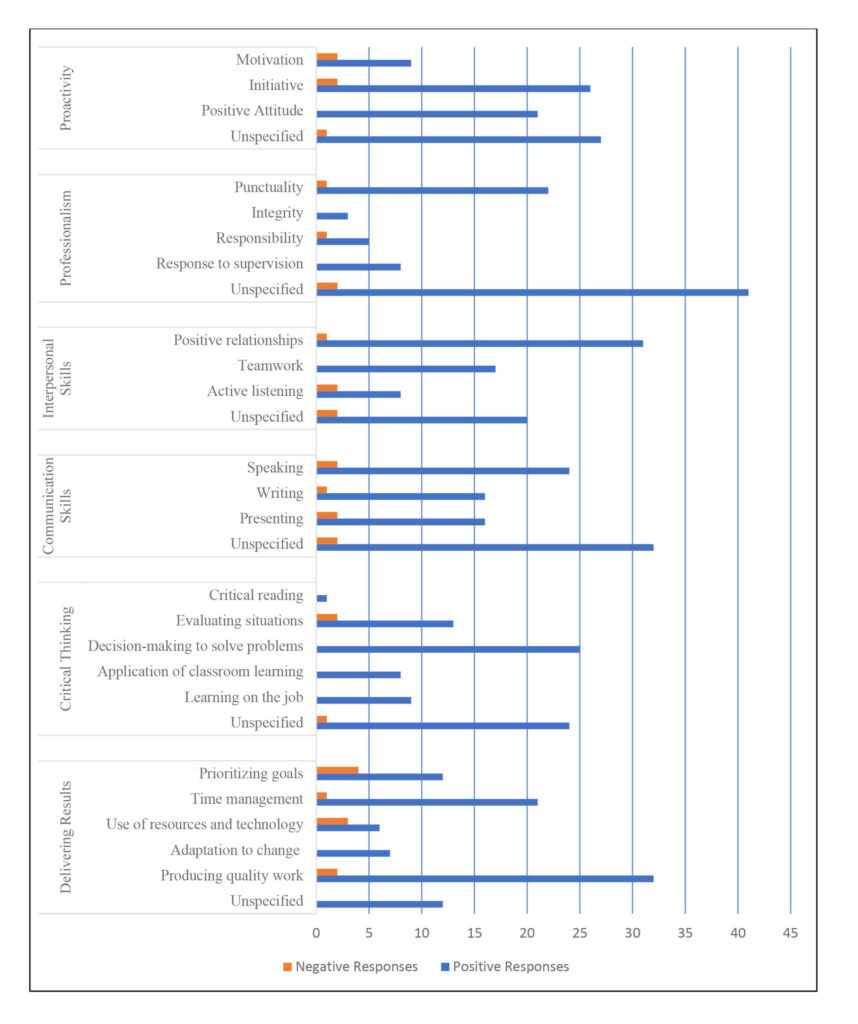

Each survey question for the key domains also ask the Internship Supervisors to explain their ratings. For example, Proactivity requested: “Please explain your answer on this student’s proactivity using examples from their internship experience.” Responses from Internship Supervisors were subjected to qualitative analysis as detailed in the Methods section above.

Findings from the analysis of open-response questions from Section 1 are shown in Figure 3, Measures of Key Domains. These data indicate that Internship Supervisors’ explanations of their rating of Student Interns were positive, as several subcategories carried only positive remarks. Giving some balance to the positive explanations is a substantial level of negative comments found in the Communication Skills and Delivering Results domains. Negative explanations were provided for all four categories from the Communication Skills domain: speaking, writing, presenting, and unspecified. This may indicate a need for the university to address communication skills for OSH Student Interns.

Figure 3, Measures of Key Domains

For the Delivering Results domain, not all categories included negative explanations. However, two categories find the most substantial number of negative comments: prioritizing goals and use of resources, with four and three negative comments, respectively. These were the highest number of negative comments of all categories across all domains. These negative comments should not be discounted but should also be taken within the context of the greater magnitude of positive comments. For example, within the Delivering Results domain, comments for the producing quality work category were determined to have thirty-two positive comments.

Results of Section 2: Count and Open Response:

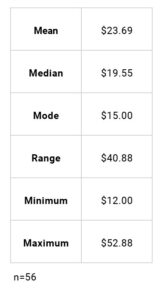

Table 2: Salary Data

Question 1 asks Internship Supervisors to provide the salary for their Student Interns as an hourly pay rate. When reported as an annual salary, the amount is converted to hourly pay to calculate the average. Fewer responses were provided for salary (n = 56) than other questions, but data gathered found that the average salary was $23.69. It is perhaps better to consider the median salary as an indicator due to some very high hourly rates, as found in Table 2, Salary Data. While the median could be considered a good wage for a Student Intern, these data did not include other benefits that some internship host employers might provide in addition to salaries, such as housing stipends, use of a company vehicle, and others. The author knows several host employers in the survey population that provided these benefits.

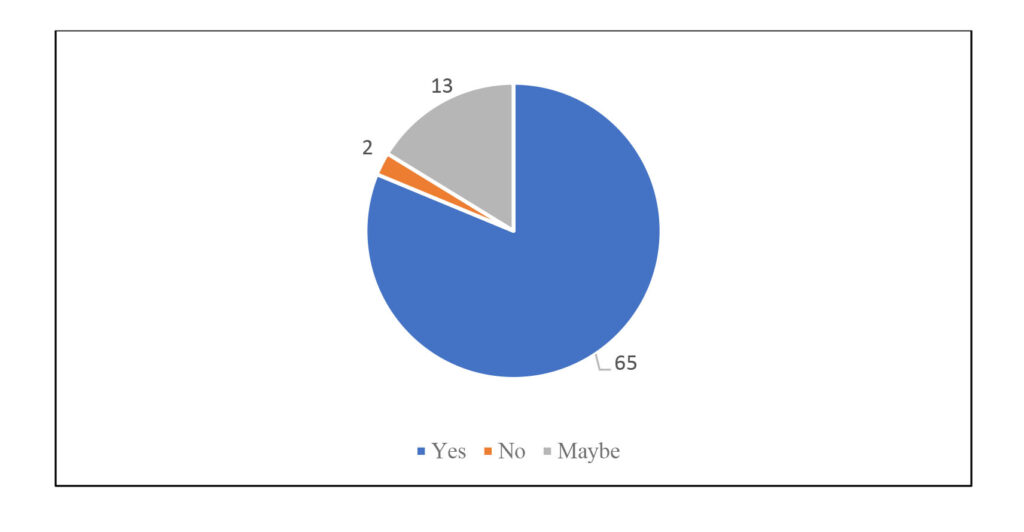

Question 2 asked: “Based on this student’s performance this semester, would you offer her/him a job if available?” The possible responses were: Yes, No, or Maybe, for which counts were reported. Internship Supervisors’ responses indicates Yes in sixty-five cases, No in two cases, and Maybe in thirteen, as shown in Figure 4, Job Offer. Findings were very encouraging and align with findings from the National Association of Colleges and Employers (2021), which reports that nearly 80% of interns receive job offers from their host employers. Note that the question included the qualifier, “if available,” which may explain the No and Maybe response findings.

Figure 4: Job Offer

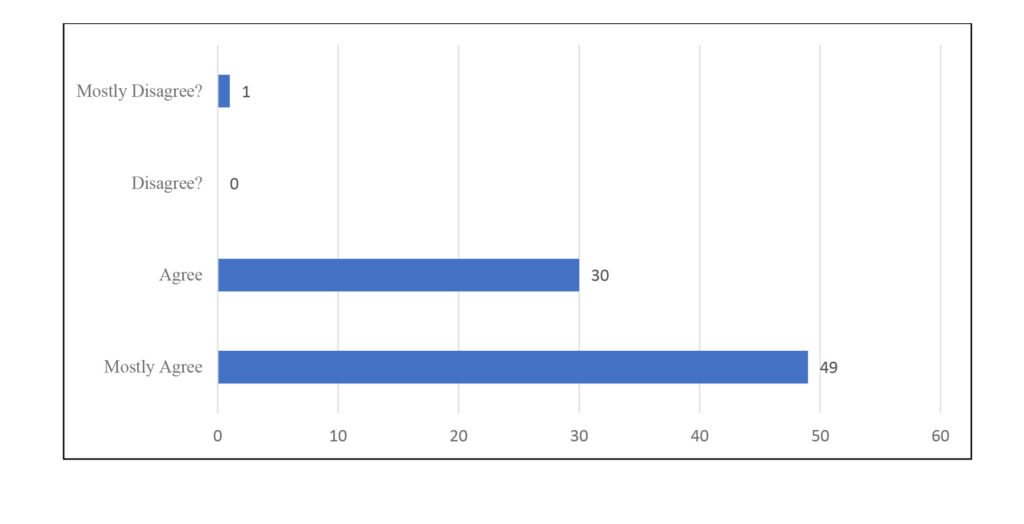

Question 3 asked Internship Supervisors to indicate their agreement with the statement: “The student’s academic program prepared them for their internship.” Agreement is measured from counts made of the possible responses of Disagree, Mostly Disagree, Mostly Agree, and Agree. Findings indicate that Internship Supervisors overwhelmingly consider that interns’ preparation was good, with seventy-nine responding Agree and Mostly Agree, 1 with Mostly Disagree, and 0 with Disagree, as shown in Figure 5, Academic Preparation. These responses indicate that these Internship Supervisors considered their interns to be academically prepared for their internships, a positive reflection on the university. This is not to say that the university could not make improvements towards better preparing students, as other measures in this study, such as those associated with soft skills detailed below, may indicate such opportunities.

Figure 5: Academic Preparation

The final question, “What are your suggestions for this student’s professional development?” generates open responses. Supervisors’ responses are quantitatively analyzed using a process in which common themes are first identified. After review, responses are determined to fall into three themes, all of which involved courses of action relating to expanding or refining the following: knowledge, skills, and abilities; soft skills; and career success endeavors. The open responses are then categorized into one or more themes and tabulated to arrive at a count for each.

Findings regarding Internship Supervisors’ suggestions for student professional development indicates that responses related to the knowledge, skills, and abilities (KSA’s) theme are most recommended, while the remainder of responses were nearly split between soft skills and career success endeavors. These data suggest that the university should focus efforts primarily on applicable KSA’s.

Conclusion

This study presents an analysis of the performance of OSH Student Interns, according to survey responses provided by their Internship Supervisors. The study also describes the key details of internships completed by students enrolled in occupational safety and health degree programs at Eastern Kentucky University. Analysis of data gathered from surveys spanning from Fall 2019 through Fall 2021 indicates that the OSH interns’ performance is largely well-regarded by Internship Supervisors. However, to better understand OSH internships, additional study is needed. More detailed information could be gathered from Internship Supervisors through direct interviews or through the utilization of focus groups. Such efforts should be given high priority among stakeholders, as internships offer substantial benefits to students, host employers, and the universities. Page Break

References

Ambrose, S. A., & Poklop, L. (2015). Do students really learn from experience? Change, 47(1), 54–61.

https://doi.org.libproxy.eku.edu/10.1080/00091383.2015.996098

American Association of Colleges and Universities. (2022). High-impact educational practices: Internships.

https://www.aacu.org/trending-topics/high-impact

Arum, R. & Roska, J. (2011). Academically Adrift: Limited Learning on College Campuses. University of Chicago Press.

https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/A/bo10327226.html

Bane, H. H. (2018). Internships are key to building talent pipeline. Crain’s Cleveland Business,

39(33), 9.

Bender, D. (2020). Education and career skills acquired during a design internship. International

Journal of Teaching & Learning in Higher Education, 32(3), 358–366.

https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1299968.pdf

Board of Certified Safety Professionals & National Safety Council. (2020). 2020 SH&E industry salary survey.

https://www.bcsp.org/safety-salary-survey/

Bowen, T., & Drysdale, M. (2017). Work-Integrated Learning in the 21st Century: Global Perspectives on the Future. Emerald Publishing Limited.

https://books.emeraldinsight.com/resources/pdfs/chapters/9781787148604-TYPE23-NR2.pdf

Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor. (2021). Occupational Outlook Handbook: Occupational Health and Safety Specialists and Technicians.

https://www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/occupational-health-and-safety-specialists-and-technicians.htm

Collins, M. (2021). Intern conversion rate climbs, fueled by jump in offer rate.

Cowles, E. L. (2019). An Introduction to survey research (2nd ed.). Business Expert Press.

https://www.businessexpertpress.com/books/an-introduction-to-survey-research-second-edition/

Derrick, D. & Fender, D. (2009). Safety 2009 Proceedings. 762. The Value of SH&E Interns for Companies. ASSE Professional Development Conference and Exhibition, 28 June-1 July, San Antonio, Texas.

https://aeasseincludes.assp.org/proceedings/2009/session.php?id=762

Eastern Kentucky University. Office of Academic and Career Services. (2021). Co-op/Internship Guidelines.

https://oacs.eku.edu/co-opinternship-guidelines

Fender, D. & Watson. L. (2005). OSH internships. Professional Safety, 50(4), 36–40.

https://aeasseincludes.assp.org/professionalsafety/pastissues/050/04/030405as.pdf

Ferguson, L. H. (1998). Guidelines for a safety internship program in industry. Professional Safety, 43(4), 22.

https://www.proquest.com/openview/56ae3f57b91178357002ad32af1f6b36/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=47267

Galbraith, D., & Mondal, S. (2020). The potential power of internships and the impact on career

preparation. Research in Higher Education Journal, 38.

https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1263677

Gardner, P. (2021). Michigan State University 51st annual recruiting trends survey & report. Michigan State University Collegiate Employment Research Institute.

https://ceri.msu.edu/recruiting-trends/recruiting-trends-2021-2022.html

Garvey, D., & Vorsteg, A. C. (1992). From theory to practice for college student interns: A stage theory approach. Journal of Experiential Education, 15(2), 40–43.

https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.1030.5891&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Gray, K. (2021). Internship experience the top differentiator when choosing between otherwise equal job candidates.

Green, M. (2019). A talent advantage. Best’s Review, 120(2), 60–63.

https://news.ambest.com/articlecontent.aspx?pc=1009&AltSrc=108&refnum=282064

Greene, M.V. (2014). How to find the perfect internship: Corporations seeking to fill talent

pipelines. U.S. Black Engineer and Information Technology, 38(3), 26–27.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/43773151#metadata_info_tab_contents

Hale, A. R., Piney, M., & Alesbury, R. J. (1986). The development of occupational hygiene and the training of health and safety professionals. The Annals of Occupational Hygiene, 30(1), 1–18.

Hora, M., Chen, Z., Parrott, E., & Her, P. (2020). Problematizing college internships: Exploring issues with access, program design and developmental outcomes. International Journal of Work-Integrated Learning, 21(3), 235–252.

https://www.ijwil.org/files/IJWIL_21_3_235_252.pdf

Hudson, D., & Ramsay, J. D. (2019). A roadmap to professionalism: Advancing occupational safety and health practice as a profession in the United States. Safety Science, 118, 168–180.

https://www.cabdirect.org/globalhealth/abstract/20193353686

Iske Jr., Allen S. D., Weller, G. & Lengfellner, L. (2017). Safety internships: Are student prepared? Professional Safety, 62(7), 36–43.

Karji, A., Bernstein, S., Tafazzoli, M., Taghinezhad, A., & Mohammadi, A. (2020). Evaluation of an Interview-Based Internship Class in the Construction Management Curriculum: A Case Study of the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Education Sciences, 10.

https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1017&context=constructionmgmt

Madigan, C., Johnstone, K., Cook, M., & Brandon, J. (2019). Do student internships build capability? What OHS graduates really think. Safety Science, 111, 102–110.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2018.10.003

McGlothin Jr., C. W. (2003). OS&H internships. Professional Safety, 48(6), 41.

National Association of Colleges and Employers. (2021). Class Of 2020 Interns Saw High Rate of Job Offers.

Neill, N. O. (2010). Internships as a high-impact practice: Some reflections on quality. Peer Review, 12(4), 4–8.

Niman, N. B., & Chagnon, J. R. (2021). Redesigning the future of experiential learning. Journal of Higher Education Theory & Practice, 21(8), 87–98.

https://businessinpractice.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Future-of-Exp-Learning.pdf

Scheuer, C.-L., & Mills, A. J. (2016). Discursivity and Media Constructions of the Intern: Implications for Pedagogy and Practice. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 15(3), 456–470.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/44074742#metadata_info_tab_contents

Tucciarone, K. (2014). How universities can increase enrollment by advertising internships. College & University, 90(2), 28–38.

https://www.proquest.com/docview/1701736850

Velez, G. S., & Giner, G. R. (2015). Effects of business internships on students, employers, and higher education institutions: A systematic review. Journal of Employment Counseling, 52(3), 121–130.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/joec.12010

Weible, R. (2009). Are universities reaping the available benefits internship programs offer? Journal of Education for Business, 85(2), 59–63.

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/08832320903252397

Weible, R., & McClure, R. (2014). An exploration of the benefits of student internships to marketing departments. Marketing Education Review, 21(3), 229–240.

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.2753/MER1052-8008210303

Wybo, J.L., & Van Wassenhove, W. (2016). Preparing graduate students to be HSE professionals. Safety Science, 81, 25–34.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0925753515000983

About Dr. David Stumbo

Dr. Stumbo is an Associate Professor in Eastern Kentucky University’s Department of Safety, Security, Faculty Internship Coordinator, and a practicing occupational safety and health consultant.